Near-duplicate image search

Author: Sayak Paul

Date created: 2021/09/10

Last modified: 2023/08/30

Description: Building a near-duplicate image search utility using deep learning and locality-sensitive hashing.

Introduction

Fetching similar images in (near) real time is an important use case of information retrieval systems. Some popular products utilizing it include Pinterest, Google Image Search, etc. In this example, we will build a similar image search utility using Locality Sensitive Hashing (LSH) and random projection on top of the image representations computed by a pretrained image classifier. This kind of search engine is also known as a near-duplicate (or near-dup) image detector. We will also look into optimizing the inference performance of our search utility on GPU using TensorRT.

There are other examples under keras.io/examples/vision that are worth checking out in this regard:

- Metric learning for image similarity search

- Image similarity estimation using a Siamese Network with a triplet loss

Finally, this example uses the following resource as a reference and as such reuses some of its code: Locality Sensitive Hashing for Similar Item Search.

Note that in order to optimize the performance of our parser, you should have a GPU runtime available.

Setup

!pip install tensorrt

Imports

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import tensorflow as tf

import tensorrt

import numpy as np

import time

import tensorflow_datasets as tfds

tfds.disable_progress_bar()

Load the dataset and create a training set of 1,000 images

To keep the run time of the example short, we will be using a subset of 1,000 images from

the tf_flowers dataset (available through

TensorFlow Datasets)

to build our vocabulary.

train_ds, validation_ds = tfds.load(

"tf_flowers", split=["train[:85%]", "train[85%:]"], as_supervised=True

)

IMAGE_SIZE = 224

NUM_IMAGES = 1000

images = []

labels = []

for (image, label) in train_ds.take(NUM_IMAGES):

image = tf.image.resize(image, (IMAGE_SIZE, IMAGE_SIZE))

images.append(image.numpy())

labels.append(label.numpy())

images = np.array(images)

labels = np.array(labels)

Load a pre-trained model

In this section, we load an image classification model that was trained on the

tf_flowers dataset. 85% of the total images were used to build the training set. For

more details on the training, refer to

this notebook.

The underlying model is a BiT-ResNet (proposed in Big Transfer (BiT): General Visual Representation Learning). The BiT-ResNet family of models is known to provide excellent transfer performance across a wide variety of different downstream tasks.

!wget -q https://github.com/sayakpaul/near-dup-parser/releases/download/v0.1.0/flower_model_bit_0.96875.zip

!unzip -qq flower_model_bit_0.96875.zip

bit_model = tf.keras.models.load_model("flower_model_bit_0.96875")

bit_model.count_params()

23510597

Create an embedding model

To retrieve similar images given a query image, we need to first generate vector representations of all the images involved. We do this via an embedding model that extracts output features from our pretrained classifier and normalizes the resulting feature vectors.

embedding_model = tf.keras.Sequential(

[

tf.keras.layers.Input((IMAGE_SIZE, IMAGE_SIZE, 3)),

tf.keras.layers.Rescaling(scale=1.0 / 255),

bit_model.layers[1],

tf.keras.layers.Normalization(mean=0, variance=1),

],

name="embedding_model",

)

embedding_model.summary()

Model: "embedding_model"

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

rescaling (Rescaling) (None, 224, 224, 3) 0

_________________________________________________________________

keras_layer (KerasLayer) (None, 2048) 23500352

_________________________________________________________________

normalization (Normalization (None, 2048) 0

=================================================================

Total params: 23,500,352

Trainable params: 23,500,352

Non-trainable params: 0

_________________________________________________________________

Take note of the normalization layer inside the model. It is used to project the representation vectors to the space of unit-spheres.

Hashing utilities

def hash_func(embedding, random_vectors):

embedding = np.array(embedding)

# Random projection.

bools = np.dot(embedding, random_vectors) > 0

return [bool2int(bool_vec) for bool_vec in bools]

def bool2int(x):

y = 0

for i, j in enumerate(x):

if j:

y += 1 << i

return y

The shape of the vectors coming out of embedding_model is (2048,), and considering practical

aspects (storage, retrieval performance, etc.) it is quite large. So, there arises a need

to reduce the dimensionality of the embedding vectors without reducing their information

content. This is where random projection comes into the picture.

It is based on the principle that if the

distance between a group of points on a given plane is approximately preserved, the

dimensionality of that plane can further be reduced.

Inside hash_func(), we first reduce the dimensionality of the embedding vectors. Then

we compute the bitwise hash values of the images to determine their hash buckets. Images

having same hash values are likely to go into the same hash bucket. From a deployment

perspective, bitwise hash values are cheaper to store and operate on.

Query utilities

The Table class is responsible for building a single hash table. Each entry in the hash

table is a mapping between the reduced embedding of an image from our dataset and a

unique identifier. Because our dimensionality reduction technique involves randomness, it

can so happen that similar images are not mapped to the same hash bucket everytime the

process run. To reduce this effect, we will take results from multiple tables into

consideration – the number of tables and the reduction dimensionality are the key

hyperparameters here.

Crucially, you wouldn't reimplement locality-sensitive hashing yourself when working with real world applications. Instead, you'd likely use one of the following popular libraries:

class Table:

def __init__(self, hash_size, dim):

self.table = {}

self.hash_size = hash_size

self.random_vectors = np.random.randn(hash_size, dim).T

def add(self, id, vectors, label):

# Create a unique indentifier.

entry = {"id_label": str(id) + "_" + str(label)}

# Compute the hash values.

hashes = hash_func(vectors, self.random_vectors)

# Add the hash values to the current table.

for h in hashes:

if h in self.table:

self.table[h].append(entry)

else:

self.table[h] = [entry]

def query(self, vectors):

# Compute hash value for the query vector.

hashes = hash_func(vectors, self.random_vectors)

results = []

# Loop over the query hashes and determine if they exist in

# the current table.

for h in hashes:

if h in self.table:

results.extend(self.table[h])

return results

In the following LSH class we will pack the utilities to have multiple hash tables.

class LSH:

def __init__(self, hash_size, dim, num_tables):

self.num_tables = num_tables

self.tables = []

for i in range(self.num_tables):

self.tables.append(Table(hash_size, dim))

def add(self, id, vectors, label):

for table in self.tables:

table.add(id, vectors, label)

def query(self, vectors):

results = []

for table in self.tables:

results.extend(table.query(vectors))

return results

Now we can encapsulate the logic for building and operating with the master LSH table (a collection of many tables) inside a class. It has two methods:

train(): Responsible for building the final LSH table.query(): Computes the number of matches given a query image and also quantifies the similarity score.

class BuildLSHTable:

def __init__(

self,

prediction_model,

concrete_function=False,

hash_size=8,

dim=2048,

num_tables=10,

):

self.hash_size = hash_size

self.dim = dim

self.num_tables = num_tables

self.lsh = LSH(self.hash_size, self.dim, self.num_tables)

self.prediction_model = prediction_model

self.concrete_function = concrete_function

def train(self, training_files):

for id, training_file in enumerate(training_files):

# Unpack the data.

image, label = training_file

if len(image.shape) < 4:

image = image[None, ...]

# Compute embeddings and update the LSH tables.

# More on `self.concrete_function()` later.

if self.concrete_function:

features = self.prediction_model(tf.constant(image))[

"normalization"

].numpy()

else:

features = self.prediction_model.predict(image)

self.lsh.add(id, features, label)

def query(self, image, verbose=True):

# Compute the embeddings of the query image and fetch the results.

if len(image.shape) < 4:

image = image[None, ...]

if self.concrete_function:

features = self.prediction_model(tf.constant(image))[

"normalization"

].numpy()

else:

features = self.prediction_model.predict(image)

results = self.lsh.query(features)

if verbose:

print("Matches:", len(results))

# Calculate Jaccard index to quantify the similarity.

counts = {}

for r in results:

if r["id_label"] in counts:

counts[r["id_label"]] += 1

else:

counts[r["id_label"]] = 1

for k in counts:

counts[k] = float(counts[k]) / self.dim

return counts

Create LSH tables

With our helper utilities and classes implemented, we can now build our LSH table. Since we will be benchmarking performance between optimized and unoptimized embedding models, we will also warm up our GPU to avoid any unfair comparison.

# Utility to warm up the GPU.

def warmup():

dummy_sample = tf.ones((1, IMAGE_SIZE, IMAGE_SIZE, 3))

for _ in range(100):

_ = embedding_model.predict(dummy_sample)

Now we can first do the GPU wam-up and proceed to build the master LSH table with

embedding_model.

warmup()

training_files = zip(images, labels)

lsh_builder = BuildLSHTable(embedding_model)

lsh_builder.train(training_files)

At the time of writing, the wall time was 54.1 seconds on a Tesla T4 GPU. This timing may vary based on the GPU you are using.

Optimize the model with TensorRT

For NVIDIA-based GPUs, the

TensorRT framework

can be used to dramatically enhance the inference latency by using various model

optimization techniques like pruning, constant folding, layer fusion, and so on. Here we

will use the

tf.experimental.tensorrt

module to optimize our embedding model.

# First serialize the embedding model as a SavedModel.

embedding_model.save("embedding_model")

# Initialize the conversion parameters.

params = tf.experimental.tensorrt.ConversionParams(

precision_mode="FP16", maximum_cached_engines=16

)

# Run the conversion.

converter = tf.experimental.tensorrt.Converter(

input_saved_model_dir="embedding_model", conversion_params=params

)

converter.convert()

converter.save("tensorrt_embedding_model")

WARNING:tensorflow:Compiled the loaded model, but the compiled metrics have yet to be built. `model.compile_metrics` will be empty until you train or evaluate the model.

WARNING:tensorflow:Compiled the loaded model, but the compiled metrics have yet to be built. `model.compile_metrics` will be empty until you train or evaluate the model.

INFO:tensorflow:Assets written to: embedding_model/assets

INFO:tensorflow:Assets written to: embedding_model/assets

INFO:tensorflow:Linked TensorRT version: (0, 0, 0)

INFO:tensorflow:Linked TensorRT version: (0, 0, 0)

INFO:tensorflow:Loaded TensorRT version: (0, 0, 0)

INFO:tensorflow:Loaded TensorRT version: (0, 0, 0)

INFO:tensorflow:Assets written to: tensorrt_embedding_model/assets

INFO:tensorflow:Assets written to: tensorrt_embedding_model/assets

Notes on the parameters inside of tf.experimental.tensorrt.ConversionParams():

precision_modedefines the numerical precision of the operations in the to-be-converted model.maximum_cached_enginesspecifies the maximum number of TRT engines that will be cached to handle dynamic operations (operations with unknown shapes).

To learn more about the other options, refer to the

official documentation.

You can also explore the different quantization options provided by the

tf.experimental.tensorrt module.

# Load the converted model.

root = tf.saved_model.load("tensorrt_embedding_model")

trt_model_function = root.signatures["serving_default"]

Build LSH tables with optimized model

warmup()

training_files = zip(images, labels)

lsh_builder_trt = BuildLSHTable(trt_model_function, concrete_function=True)

lsh_builder_trt.train(training_files)

Notice the difference in the wall time which is 13.1 seconds. Earlier, with the unoptimized model it was 54.1 seconds.

We can take a closer look into one of the hash tables and get an idea of how they are represented.

idx = 0

for hash, entry in lsh_builder_trt.lsh.tables[0].table.items():

if idx == 5:

break

if len(entry) < 5:

print(hash, entry)

idx += 1

145 [{'id_label': '3_4'}, {'id_label': '727_3'}]

5 [{'id_label': '12_4'}]

128 [{'id_label': '30_2'}, {'id_label': '480_2'}]

208 [{'id_label': '34_2'}, {'id_label': '132_2'}, {'id_label': '984_2'}]

188 [{'id_label': '42_0'}, {'id_label': '135_3'}, {'id_label': '436_3'}, {'id_label': '670_3'}]

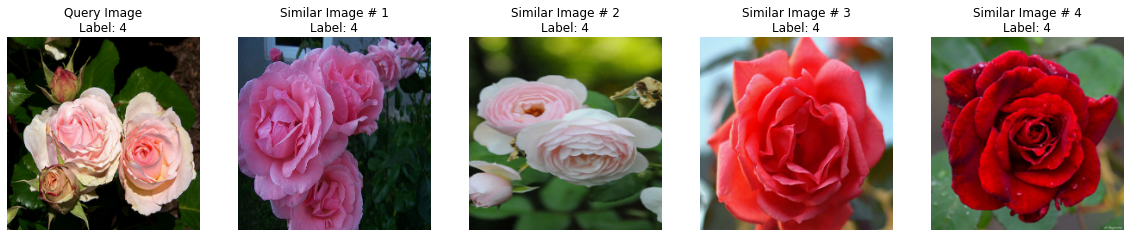

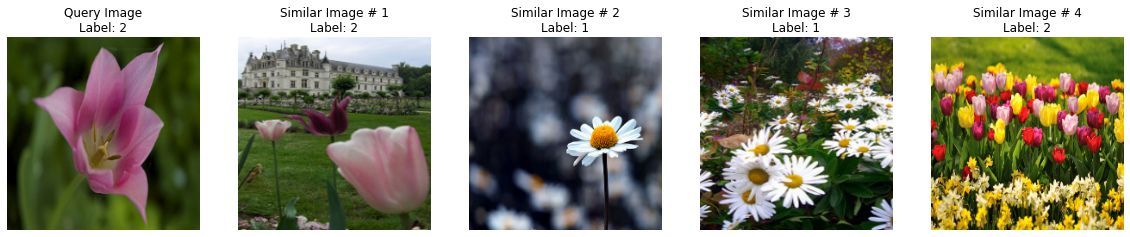

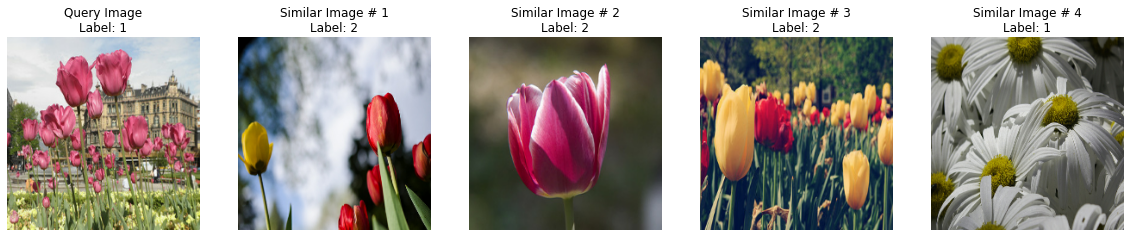

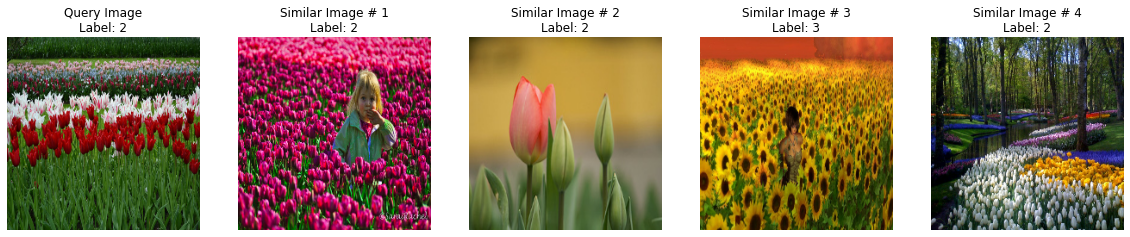

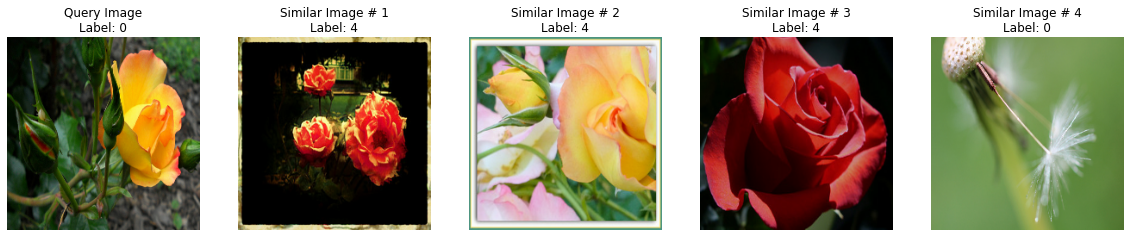

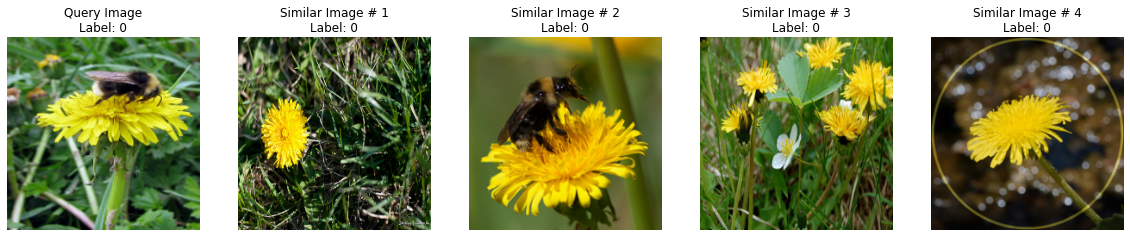

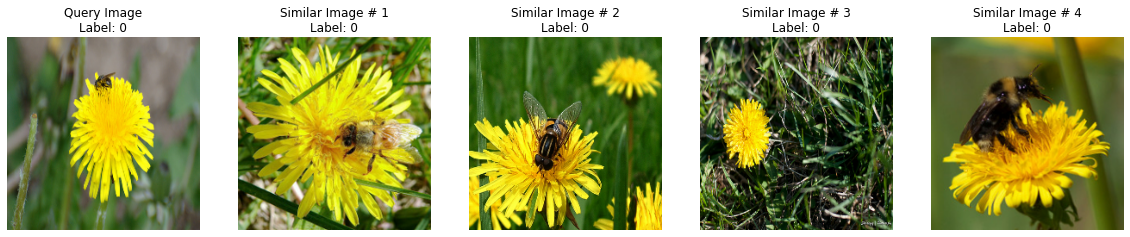

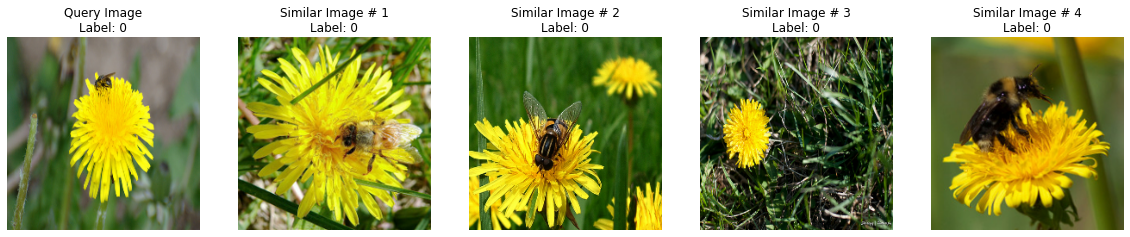

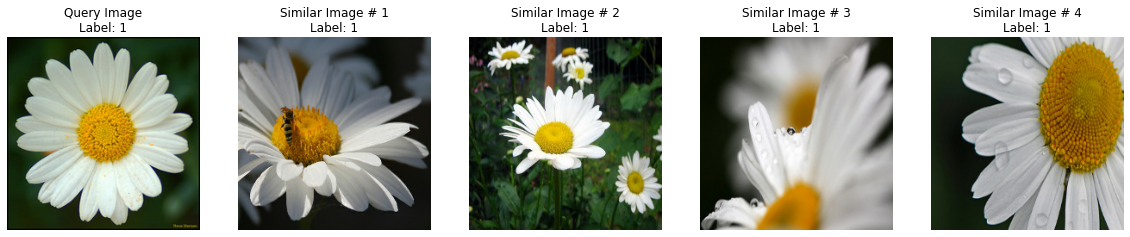

Visualize results on validation images

In this section we will first writing a couple of utility functions to visualize the similar image parsing process. Then we will benchmark the query performance of the models with and without optimization.

First, we take 100 images from the validation set for testing purposes.

validation_images = []

validation_labels = []

for image, label in validation_ds.take(100):

image = tf.image.resize(image, (224, 224))

validation_images.append(image.numpy())

validation_labels.append(label.numpy())

validation_images = np.array(validation_images)

validation_labels = np.array(validation_labels)

validation_images.shape, validation_labels.shape

((100, 224, 224, 3), (100,))

Now we write our visualization utilities.

def plot_images(images, labels):

plt.figure(figsize=(20, 10))

columns = 5

for (i, image) in enumerate(images):

ax = plt.subplot(len(images) // columns + 1, columns, i + 1)

if i == 0:

ax.set_title("Query Image\n" + "Label: {}".format(labels[i]))

else:

ax.set_title("Similar Image # " + str(i) + "\nLabel: {}".format(labels[i]))

plt.imshow(image.astype("int"))

plt.axis("off")

def visualize_lsh(lsh_class):

idx = np.random.choice(len(validation_images))

image = validation_images[idx]

label = validation_labels[idx]

results = lsh_class.query(image)

candidates = []

labels = []

overlaps = []

for idx, r in enumerate(sorted(results, key=results.get, reverse=True)):

if idx == 4:

break

image_id, label = r.split("_")[0], r.split("_")[1]

candidates.append(images[int(image_id)])

labels.append(label)

overlaps.append(results[r])

candidates.insert(0, image)

labels.insert(0, label)

plot_images(candidates, labels)

Non-TRT model

for _ in range(5):

visualize_lsh(lsh_builder)

visualize_lsh(lsh_builder)

Matches: 507

Matches: 554

Matches: 438

Matches: 370

Matches: 407

Matches: 306

TRT model

for _ in range(5):

visualize_lsh(lsh_builder_trt)

Matches: 458

Matches: 181

Matches: 280

Matches: 280

Matches: 503

As you may have noticed, there are a couple of incorrect results. This can be mitigated in a few ways:

- Better models for generating the initial embeddings especially for noisy samples. We can use techniques like ArcFace, Supervised Contrastive Learning, etc. that implicitly encourage better learning of representations for retrieval purposes.

- The trade-off between the number of tables and the reduction dimensionality is crucial and helps set the right recall required for your application.

Benchmarking query performance

def benchmark(lsh_class):

warmup()

start_time = time.time()

for _ in range(1000):

image = np.ones((1, 224, 224, 3)).astype("float32")

_ = lsh_class.query(image, verbose=False)

end_time = time.time() - start_time

print(f"Time taken: {end_time:.3f}")

benchmark(lsh_builder)

benchmark(lsh_builder_trt)

Time taken: 54.359

Time taken: 13.963

We can immediately notice a stark difference between the query performance of the two models.

Final remarks

In this example, we explored the TensorRT framework from NVIDIA for optimizing our model. It's best suited for GPU-based inference servers. There are other choices for such frameworks that cater to different hardware platforms:

- TensorFlow Lite for mobile and edge devices.

- ONNX for commodity CPU-based servers.

- Apache TVM, compiler for machine learning models covering various platforms.

Here are a few resources you might want to check out to learn more about applications based on vector similary search in general: